Sustainable Recycling: One of Five Ways to Manage Solid Waste

Recycling metal and clean cardboard makes sense, but recycling other materials is often not the best idea.

Here’s a quick take on recycling for Rotarians—and anyone else who is interested in the issue: it makes great sense to recycle metal and clean cardboard. The value of recycling anything else (especially plastics) is open for debate. Of course, preventing waste is better than recycling it.

I’m a member of Rotary International, a service organization which recently added protecting our environment to our areas of concern. I’ve been asked to chair a committee of Environmental Ambassadors for District 7780. At our first meeting, we decided to share what we know about recycling; hence this article.

Is Recycling Worth the Effort?

Recycling is a strategy to manage solid waste (“garbage” or “trash”). Municipal solid waste includes durable and nondurable goods (e.g., tires, furniture, newspapers, disposable diapers, etc.), containers and packaging (e.g., milk cartons, plastic wrap, etc.), and organic waste (e.g., yard waste, food) from households and businesses, but excludes industrial, hazardous, and construction wastes.

Between 1881 and 1895, New York City became the first city in the United States to establish an effective public trash removal system. Prior to that, garbage piled up in streets and yards. Solid waste management now accounts for 2% of state and local government direct expenditures. Some municipalities own and operate public municipal solid waste landfills, where solid waste accumulates, while others rely on waste transfer stations, which simply collect and store solid waste temporarily before sending it to its ultimate destination.

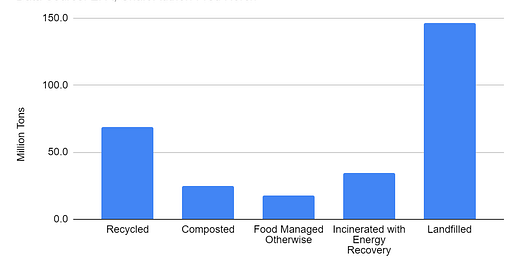

The five major strategies to manage municipal solid waste are

Landfill: bury solid waste in the ground.

Recycle: collect and process solid waste so that it can be remanufactured into new products.

Incinerate with energy recovery: burn solid waste in a thermal power plant to generate steam, which can be used for heat or electricity.

Compost: collect and manage solid waste, mixing it with water and oxygen so that microbes and other decomposing organisms can break down organic materials to produce an enriching soil amendment.

Manage food waste without composting: donate to food banks and soup kitchens, spread on land, feed animals, or use for biochemical processing.

Since 1988, dumping at sea is no longer allowed by the United States. Some solid waste ends up unmanaged as litter (and as marine debris—in 2015 there were an estimated 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris in the ocean).

All solid waste could be sent to landfills (if additional capacity is built). Whether recycling is “worth the effort” depends on your view of:

The benefits of returning material to productive use, e.g. the availability of recycled aluminum reduces the demand for energy and bauxite mines.

The relative financial cost of recycling versus other waste management strategies.

The value of hard-to-quantify environmental and social impacts (negative externalities) not reflected in financial calculations.

The value of people’s time and resources (space for recycle bins, etc.).

The impact on other waste management strategies, i.e. people worry less about reducing the packaging they buy if they can put it in a recycling bin.

The benefits of having fewer or smaller landfills.

Recycling or “Wishcycling”?

A 2020 survey by The Recycling Partnership and SWNS found that eighty-five percent of the 2,000 surveyed strongly believe in recycling and nearly 80% expect every product to be 100% recyclable in ten years. Ninety-five percent of Americans report that they recycle, and 98% of parents plan on having their child learn about recycling, according to a 2021 survey by the Paper and Packaging Board.

Americans believe in recycling so much that they often “wishcycle.”

Wishcycling is putting something in the recycling bin and hoping it will be recycled, even if there is little evidence to confirm this assumption.

Catering to people’s desire to recycle everything conveniently, a system called “single stream” recycling was pioneered in 1989 by Phoenix, Arizona, and has since been widely adopted. In Maine, ecomaine operates the state’s largest single-sort facility as well as a waste-to-energy incinerator. Single stream recycling requires a materials recovery facility (MRF) like ecomaine to separate a mix of materials, rather than sorting and separating waste streams at the source.

What MRFs actually do with material depends on market conditions. When commodity prices are high, then it makes sense to bale and send shipments for recycling. But when prices are low, it makes more sense to store, landfill, or burn mixed cardboard, paper and plastic.

Burning garbage unavoidably pollutes the air. All waste-to-energy facilities attempt to minimize pollution. Nonetheless, ecomaine’s incinerator—located near Portland’s airport—is a major source of lead and nitrous oxide air pollution in Maine.

After burning garbage and scrubbing pollution from its exhaust stack, ecomaine must truck its bottom ash and fly ash to a sanitary landfill.

What Can Actually Be Recycled?

Metal and glass can be recycled an infinite number of times without losing quality or purity. For example, the recycled content of structural steel produced in the United States is typically between 90% and 100%.

Ferrous metal contains iron; generally, it is less expensive to recycle ferrous metals than to landfill them. Aluminum, copper, gold, lead, nickel, silver, zinc and tin are non-magnetic, non-ferrous metals. Many of these metals are valuable enough that they can be sold by the pound to scrap recycling centers.

Because glass is heavy and bulky it is often cheaper to landfill it than recycle it. The Glass Recycling Coalition publishes a map of materials recovery facilities (MRFs), glass processors, and fiberglass plants. Two MRFs in Maine accept glass, but the nearest glass processors are in Montreal, Canada, and South Windsor, Connecticut.

Cardboard and paper can be recycled between five and seven times before the fibers become too short to make quality products. Cardboard packaging is a mix of virgin and recycled content; the average box in the U.S. contains 52% recycled content.

Cardboard, paper, uneaten food, eaten food (poop), sawdust, wood, yard trimmings and compostable plastics are all organic waste. Unlike metal and glass, organic waste can be composted or burned. Composting—not recycling—is usually a better idea for cardboard or paper products that have been in contact with food, such as pizza boxes.

Plastic recycling is contentious. According to The Association of Plastic Recyclers, “Recycling works.” But according to Greenpeace, “Most plastic simply cannot be recycled.” The recycling symbol and number on a plastic container does not mean that it is recyclable; it simply identifies seven categories of polymer. Some polymers can not be recycled even once while the best can be recycled ten times (although some sources claim only two or three times before they become unusable). In practice, very little plastic is actually recycled. Most is landfilled or burned.

Glossary

Aerobic decomposition—When microbes break down organic matter in the presence of oxygen, releasing carbon dioxide and water and producing humus. “Earth-Kind Landscaping, Chapter 1, The Decomposition Process”

Anaerobic digestion—When microbes break down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, often carefully controlled in sealed chambers to produce products such as biogas and soil amendments. “How Does Anaerobic Digestion Work?“

Cardboard—A common durable packaging material, usually made from quick-growing pine tree pulp and recycled cardboard. “What Is Cardboard Made of? Is Cardboard Biodegradable?”

China’s Green Fence and National Sword Programs—Chinese policies which changed the global recycling market. “Green Fence,” starting in 2013, involved more intensive inspections of incoming loads of scrap material. “National Sword” led to a 0.5% contamination limit along with an outright ban on plastics beginning in March 2018. “Impact of China’s National Sword Policy on the U.S. Landfill and Plastics Recycling Industry”

Compostable—A product that can be decomposed by micro-organisms into non-toxic, natural elements at a rate consistent with similar organic materials. “Biodegradable vs Compostable: What is the Difference?”

Composting—The natural process of recycling organic matter into a valuable fertilizer that can enrich soil and plants. “Composting 101”

Extended producer responsibility—Based on the quantity and quality of their packaging, product producers pay into a fund to reimburse municipalities for waste management costs, improve recycling infrastructure, and educate Mainers about recycling. “Extended Producer Responsibility Program for Packaging”

Glass—Can be recycled an unlimited number of times with no loss in quality, but in practice it is difficult to recycle in many areas of the United States because it is heavy and bulky and low value. “Glass Container Recycling Loop”

Materials recovery facility—A plant that separates and prepares single-stream recycling materials to be sold to end buyers. “What Is a Materials Recovery Facility (MRF)?”

Metal—Can be recycled an unlimited number of times with no loss in quality. Easier to recycle than glass. “How to Recycle Scrap Metal”

Municipal landfill—A discrete area of land or excavation that receives household waste. “Municipal Solid Waste Landfills”

Paper—An organic product that is the most recycled material in the United States, paper can also easily be composted for free in backyard bins. “Does Paper Actually Get Recycled? The Industry Answers.”

Plastic—A wide range of moldable and waterproof materials based on long polymer chains. About 5% to 6% of plastic is recycled in the United States. Recycling plastic produces microplastic pollution. “The little-known unintended consequence of recycling plastics”

Recyclable—A recycling symbol or the word “recyclable” on a product does not mean that it actually can be recycled. “Trash or Recycling? Why Plastic Keeps Us Guessing.”

Recycling—Collecting and reclaiming materials from a waste stream and using them to make new products. “Recycling 101”

Sanitary landfill—Sites where waste is isolated from the environment until it has completely degraded biologically, chemically and physically. “What is a Sanitary Landfill?”

Waste-to-energy facility—Waste-to-energy plants burn municipal solid waste to produce steam to power electric generators. “Biomass explained”

Waste transfer station—Industrial facilities where municipal solid waste is temporarily held and sorted before heading to a landfill or waste-to-energy plant. “What Really Happens at Waste Transfer Stations”

I realize that I do a fair amount of "wishcycling", and when we visit the Topsham transfer station, many items in our recycling bin are rejected and put into the landfill. Thanks for the really helpful information.

This is an incredibly comprehensive view of what consumers must consider at point of purchase and in their individual recycling efforts. This info by Fred is important for all of us to consider in our decision-making.